Voxel Level of Detail

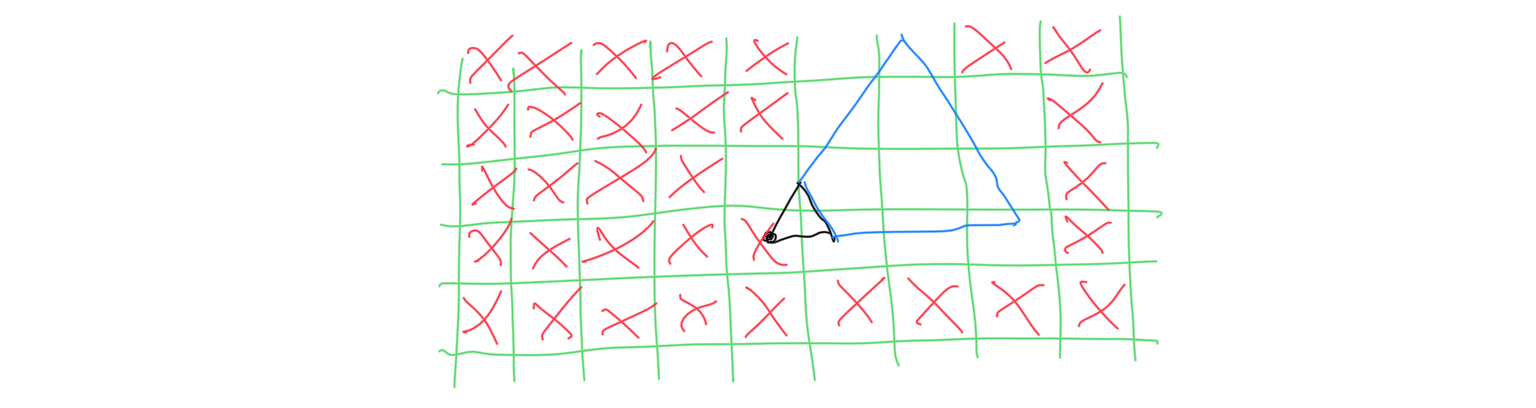

Games typically put more detail close to the player and less detail further away. This ensures the game runs smoothly, because less triangles need to be rendered if they occupy a small space on the screen. This concept is called level of detail (or LOD). Game developers forfeit their direct control over level of detail when they make their game a voxel game, but they can get around this by designing a system that can turn volumetric data into a visible mesh with a specified level of detail. The figure below shows meshes generated from the same volumetric data but different levels of detail in 2D.

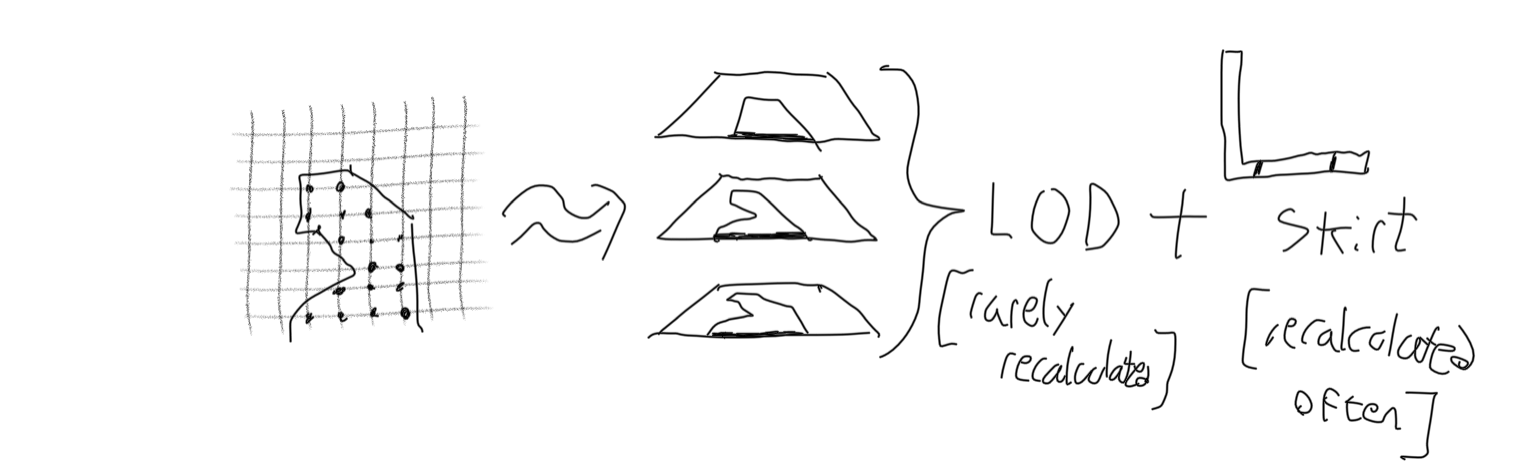

Generating a less detailed mesh isn’t terribly difficult. Each branch of the octree must store a vertex, just like the leaves do. Then, each branch with a depth X above the leaves become the new leaves, so that when the mesh generation step occurs, each 2x2x2 region behaves as one feature. In the leaves of the tree, Vertices are placed by minimizing Q(x,y,z), the sum of the squared distance to each nearby tangent plane. When grouping regions together, then, the branch must minimize the sum of each child node’s Q function. This allows vertex calculation to be done for all levels of detail recursively.

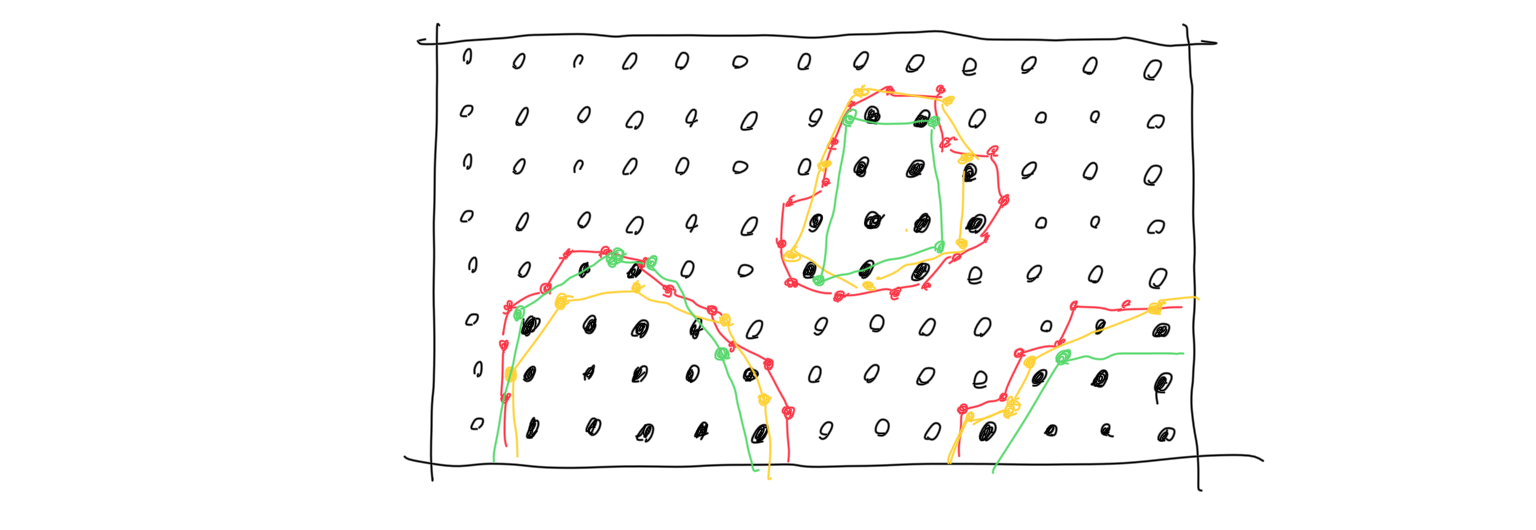

The difficult part comes when polygons must be drawn to stitch together different levels of detail. Enclosed are diagrams and examples of cases that must be handled. Extra triangles must be drawn to ensure the mesh is continuous, but that can be very difficult. Even worse, though, is that any time the level of detail on one chunk must be changed, that could result to tiny changes in the edges of up to six other meshes, requiring full recalculation of each. I solve this problem by storing the main part of the chunk separately from the skirting. The main mesh is generated in each level of detail and does not recalculate unless changed, while the skirt is recalculated each time it or one of its six relevant neighbors are changed. The skirt alone takes much less time to recalculate, and this way level of detail recalculation is minimized. The game can also load a lot more terrain before performance takes a hit, due to level of detail.

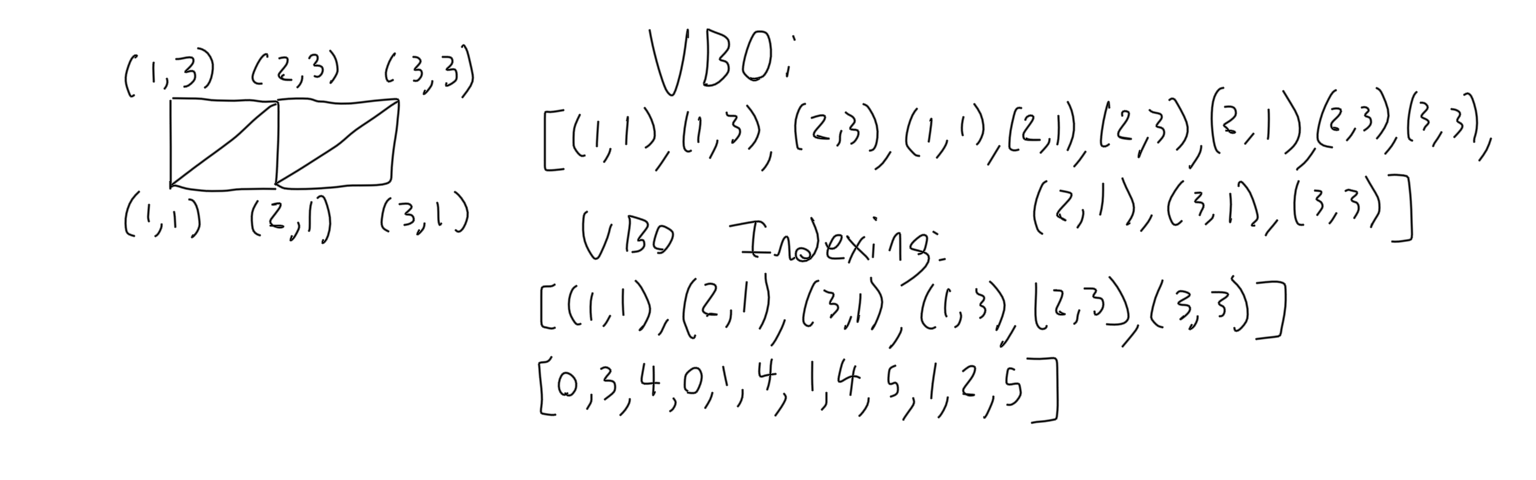

There are many other optimizations done to the game to increase performance. One of which is VBO indexing. This can decrease graphics card memory used for any application, but with dual contouring, it offers an additional benefit. Stitching between vertecies must be recalculated only when the gridlike sampling points change, but the index array does not change when hermit data changes. This means, for small changes to terrain, only part of the mesh generation must be recalculated.

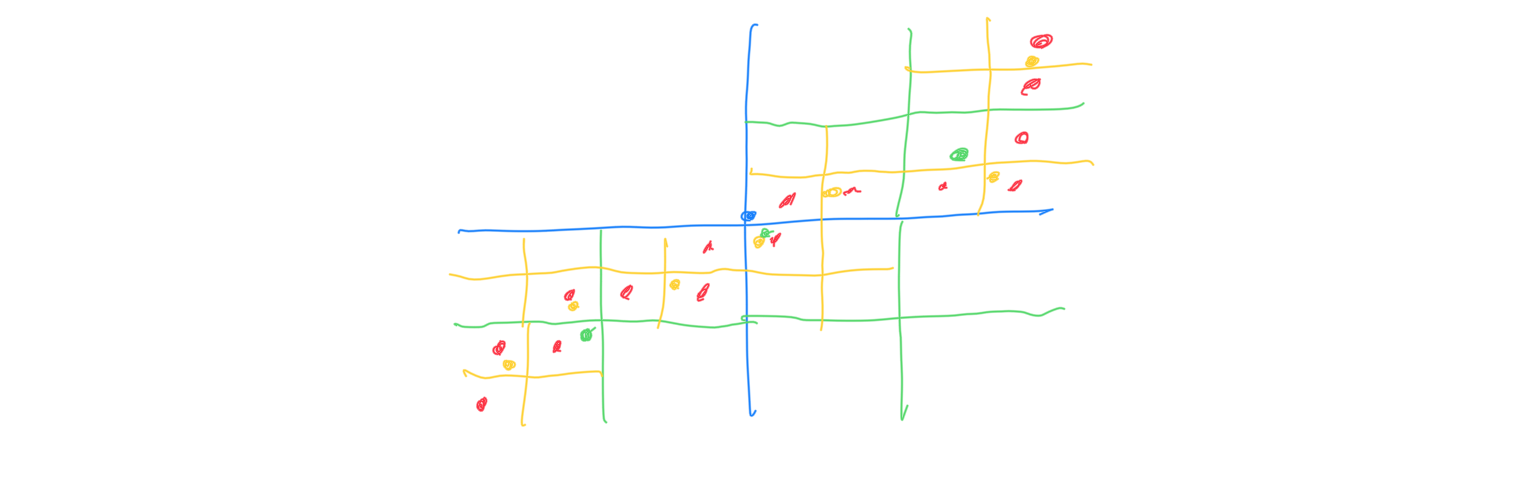

Another optimization (and by far the simplest) is called frustrum culling. The game does not need to render meshes that are outside the camera’s view, so if the game can quickly detect this, many costly draw calls can be avoided. The detection method may have false negatives, but false positives are unacceptable, because then meshes would disappear from the players view. The voxel engine does this by first extracting the top, bottom, left, right, near, and far planes from the camera’s projection matrix, and then testing if the bounding spheres of meshes lies inside those six planes. The math behind this isn’t hard- it boils down to just six dot products, some addition, and some comparison per bounding sphere. It can be tricky to debug, though, because if all is working well, the only noticeable difference is performance.