Generating Rubik's Puzzles

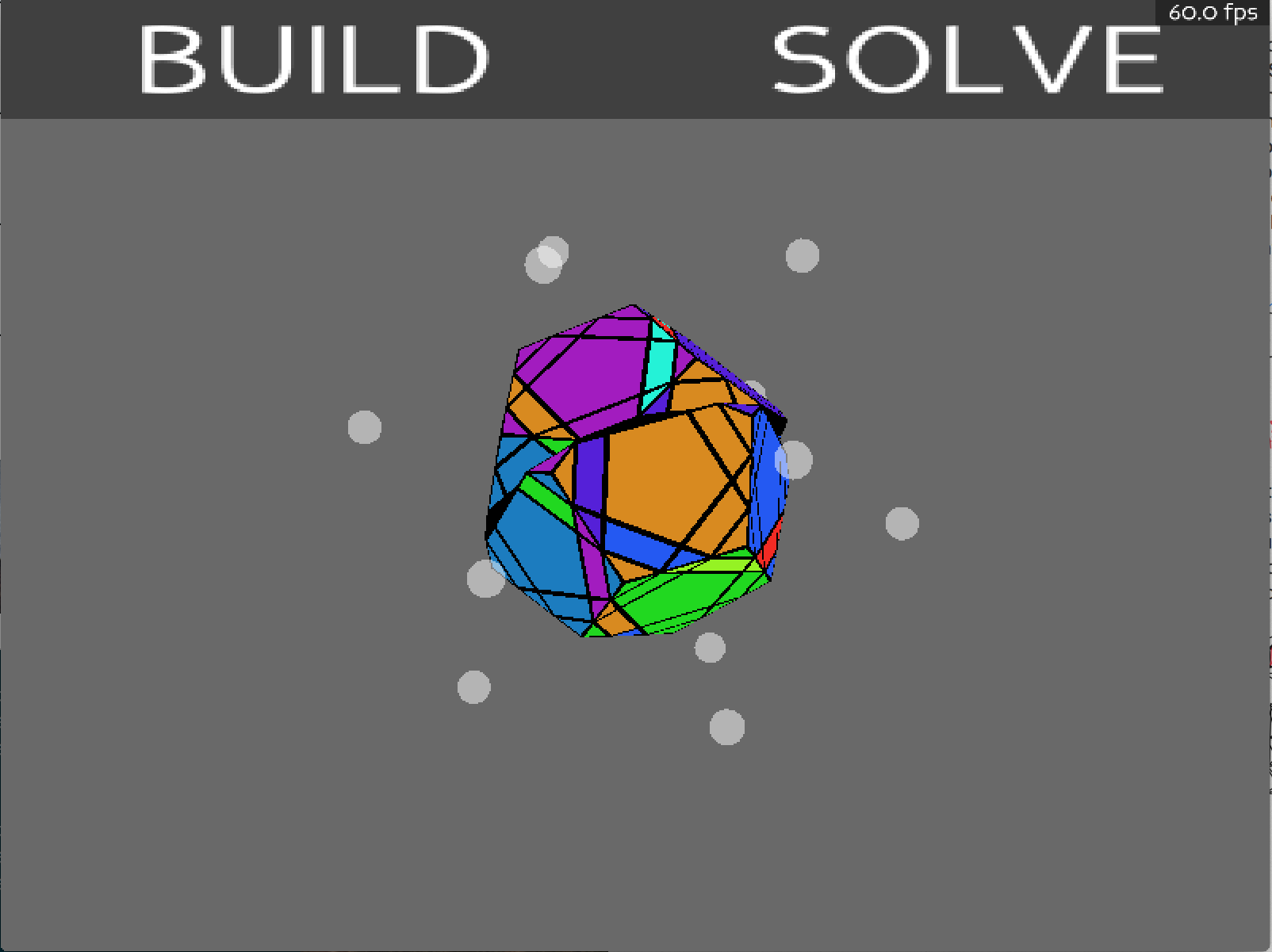

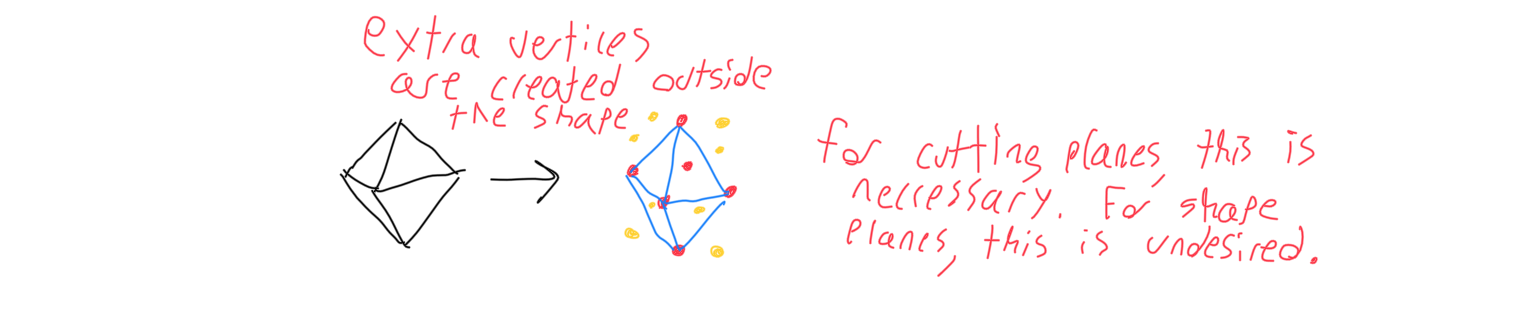

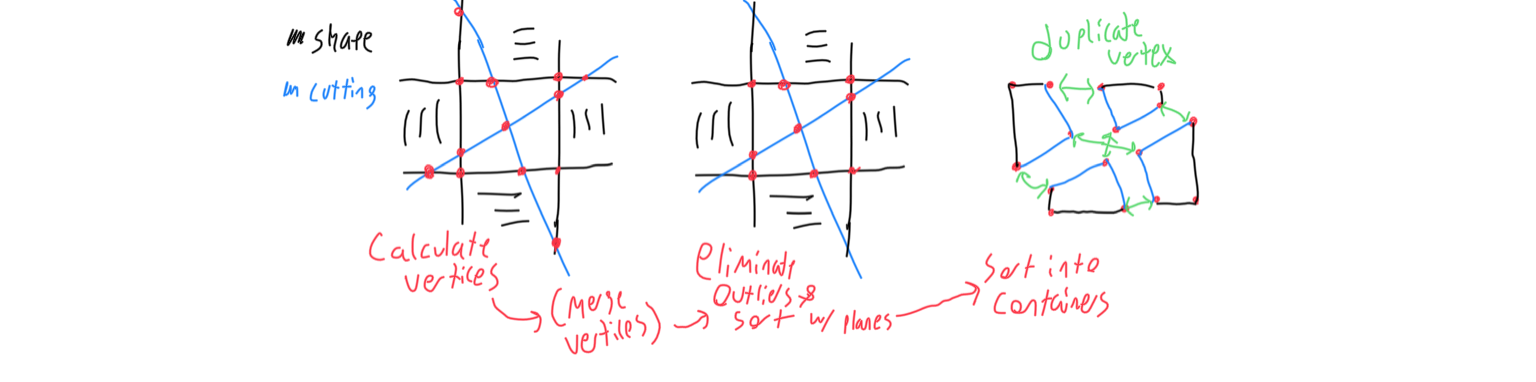

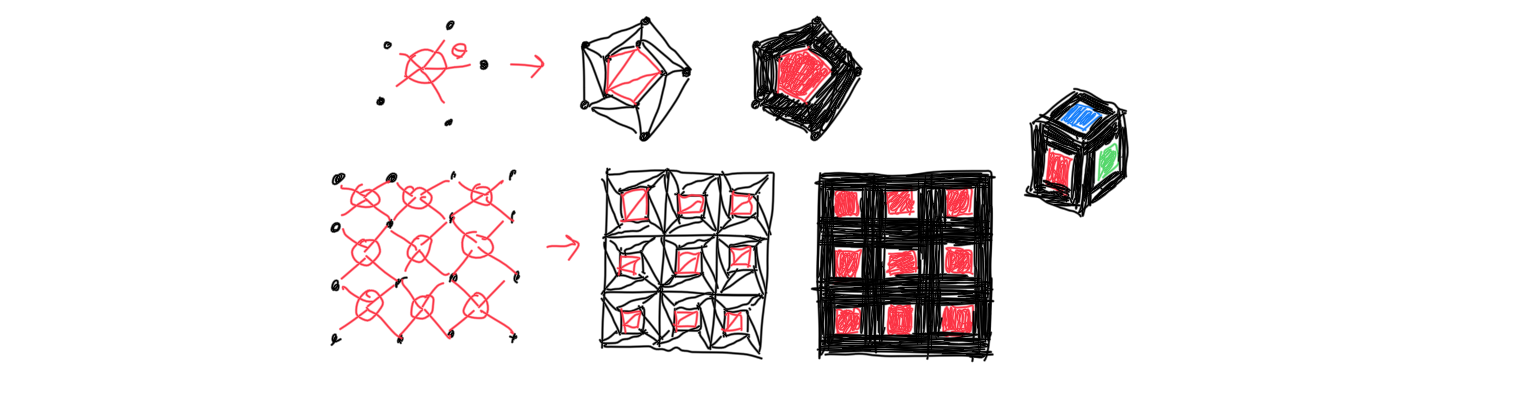

The next step for the cube generator is creating the puzzle’s visible mesh. This is done with the following process: First, each unique combination of three planes is intersected to create a vertex. This is the simplest step- it only takes some creative iteration and solving a matrix. Each vertex must remember the set of three planes created it.

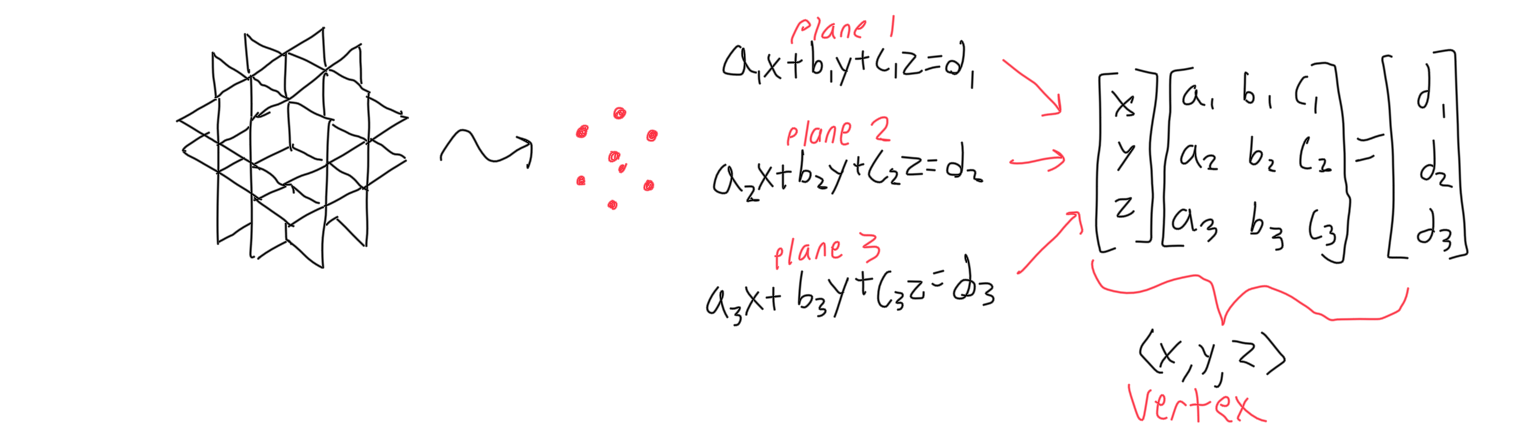

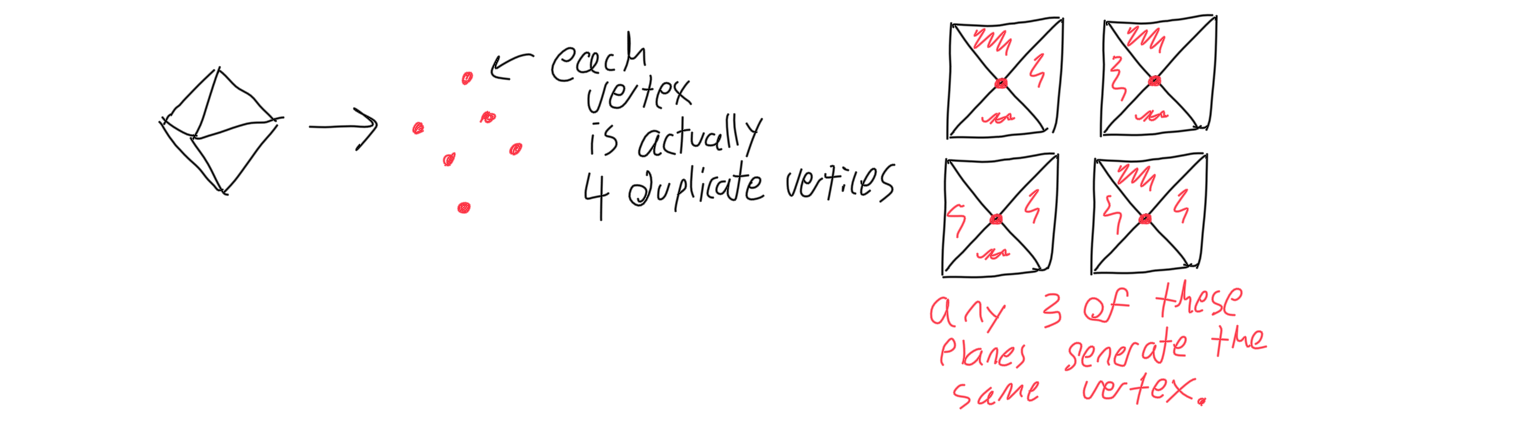

Second, vertices that are close together are merged. Shapes like the cube and tetrahedron don’t have to worry about this, but shapes like the octahedron and icosahedron have vertices that lie at the intersection of four or more planes, generating many duplicate vertices. Even the dodecahedron planes will create duplicate vertices, but those vertices lie outside the solid, so they only become relevant when those planes are cutting planes, not shape-defining planes. This part began to create performance issues, because N planes would create (n)(n-1)(n-3)/6 vertices, and V vertices would necessitate (v)(v-1)/2 duplicate checks. To improve the algorithm’s time complexity, I sorted the vertices by their x value first, and then used a creative iteration method to eliminate the vast majority of duplicate vertex checks. If two vertices are merged, the resulting vertex’s set of planes will be the union of the two that merged.

Third, each vertex must determine which side of each plane it lies on. This can be done easily in this scenario, because it turns into one dot product. Vertices are not tested against the planes that created them. If a vertex lies on the outside of a shape-defining plane, it will be eliminated. Vertices remember which cutting planes they lie outside of.

Fourth, the vertices are sorted into different containers, each container representing an indivisible piece of the puzzle. Shape planes don’t factor into this sorting process, but cutting planes do. If a puzzle has no cutting planes, then all vertices would fall into a single container. Each cutting plane multiplies the number of containers by two. Each container is divided into a container above the cutting plane, which rotates when that face is turned, and a container below it which does not. If a vertex lies above or below a cutting plane, that determines which container it falls into. If it was created by the cutting plane and therefore lies on that plane, then the vertex is duplicated and goes into both containers.

Lastly, each container is stitched together to create its visible mesh. Faces are identified as non-exclusive groups of vertices that were created by the same plane. Cross and dot products are then used to sort them with the correct winding order. If the plane that created these vertices was a shape defining plane, a copy of the face vertices are made and then scaled inwards to serve as the colored part of the mesh.

The rest of the application isn't as interesting from a mathematical point of view. Pieces of the puzzle can be dragged to rotate, or spheres can be clicked to rotate a face once. Pieces rotate if their centers lie above the cutting plane that was 'activated'.