Higher order unification

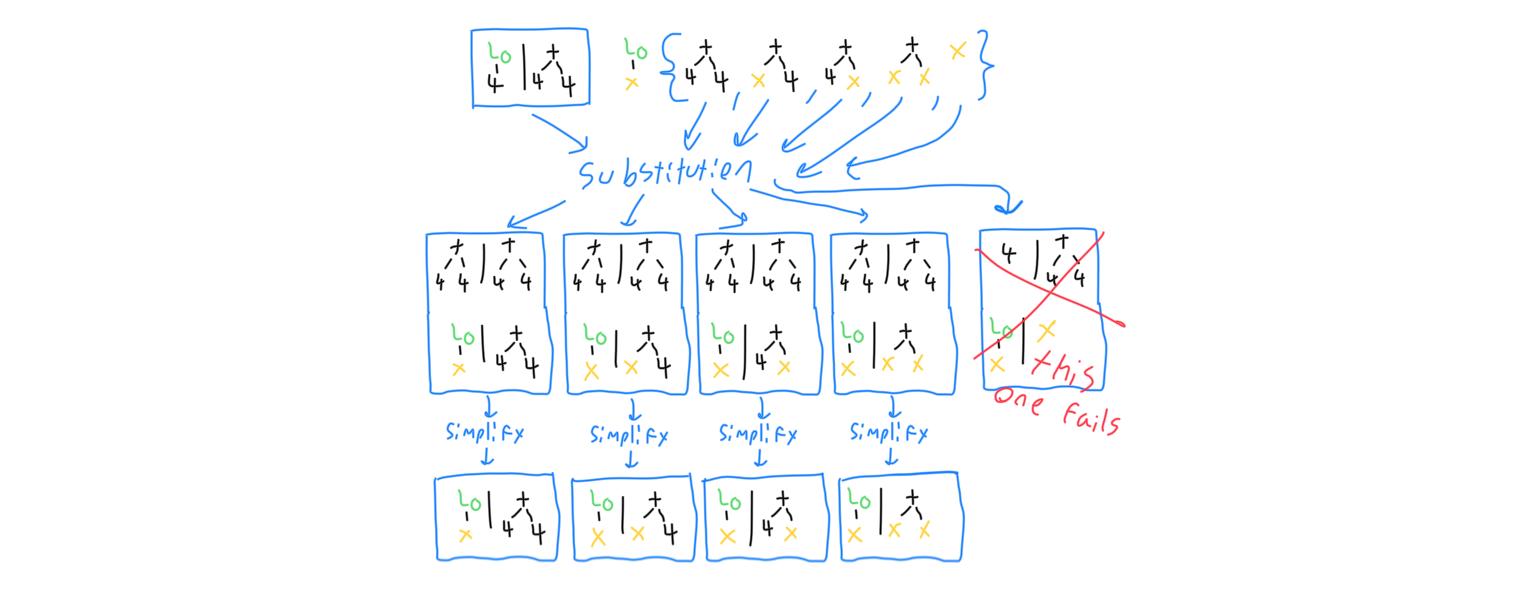

This problem is known as higher order unification, and it has a lot of nuances. After performing pattern matching, the original pair stays in the binding object, but it is joined by both the possible combination, and the types of the new combination, which I’ll get to later. The new pair and the original pair can always substitute, just like the last simplification step. They key is that each possibility produced by the pattern matcher may or may not work as a generalization of the original pair. The following steps weed out the incorrect patterns.

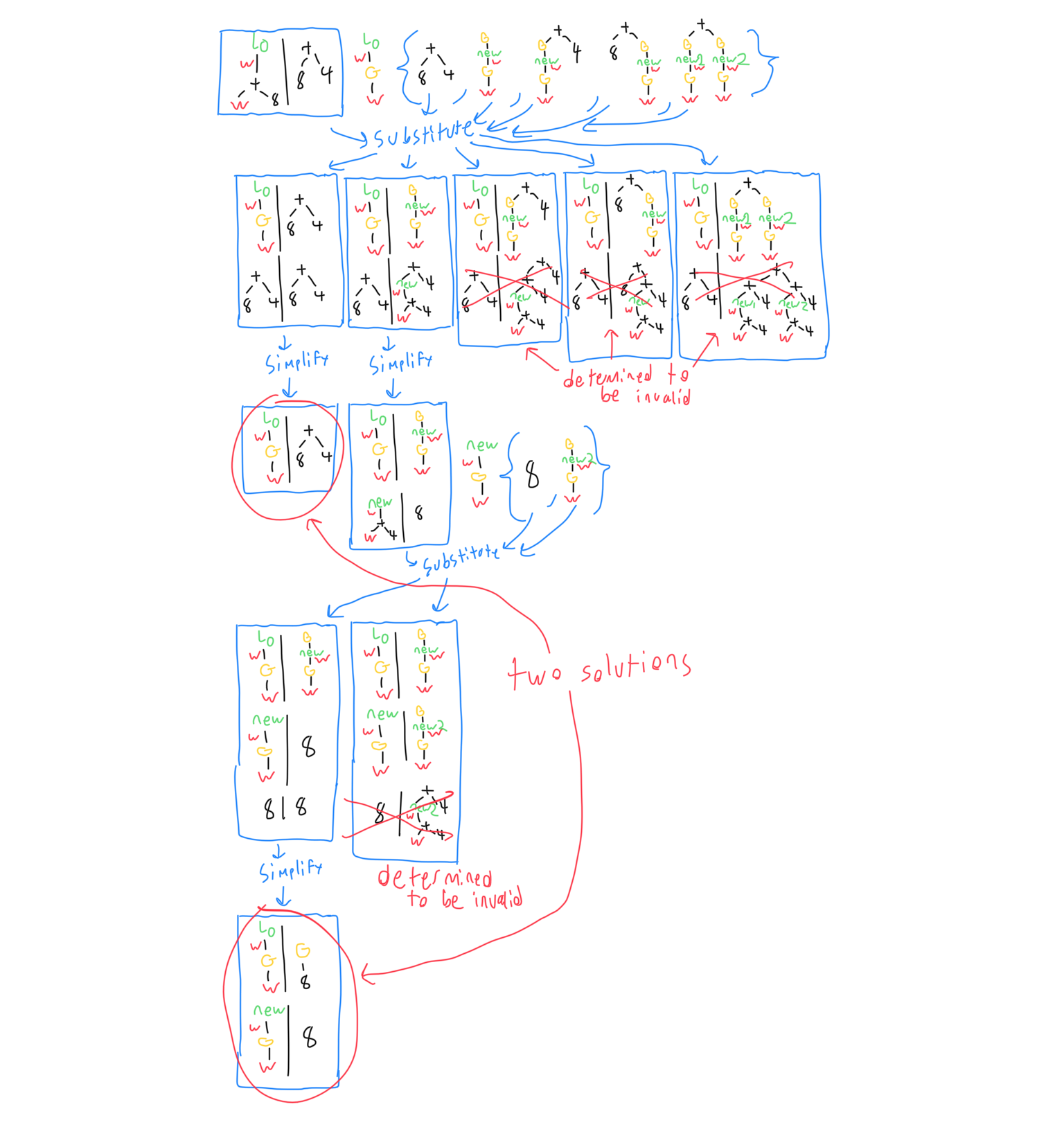

The expression on the left for the generalization that fully specifies the unknown variable is easy to come up with for simple functions like the one described above. Unknowns with more complicated type signatures, on the other hand, have a more complicated process involved. Below is an example of how higher order unification works for unknown functions whose argument is also a function. New unknowns may be created in the resulting patterns, which often end up being solved once the resulting binding objects are substituted. It must be done this way, because sometimes the binding object ends up with no information about the spot in the pattern where the new unknowns are, so that spot must be stored as an unknown.

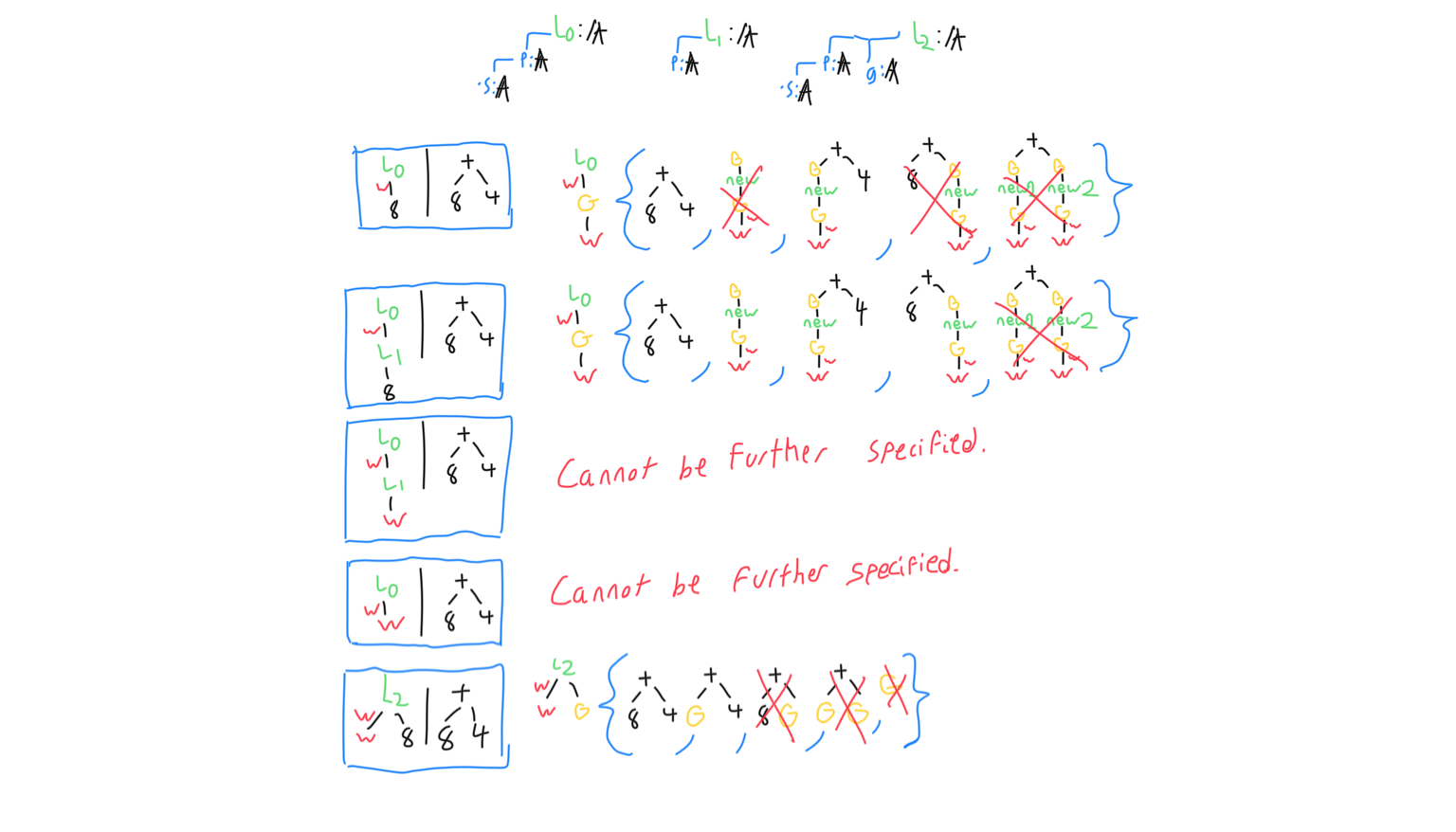

Among pairs where the unknown is a function whose argument is a function, there are examples which cannot be fully generalized. In particular, anytime a parameter is the identity function, or could possibly be the identity function, there would be infinitely many solutions for the fully generalized expression. The most simplified expression possible, in those situations, involves generalizing any other parameter, but leaving the identity functions alone. Below is a table that shows what I mean.

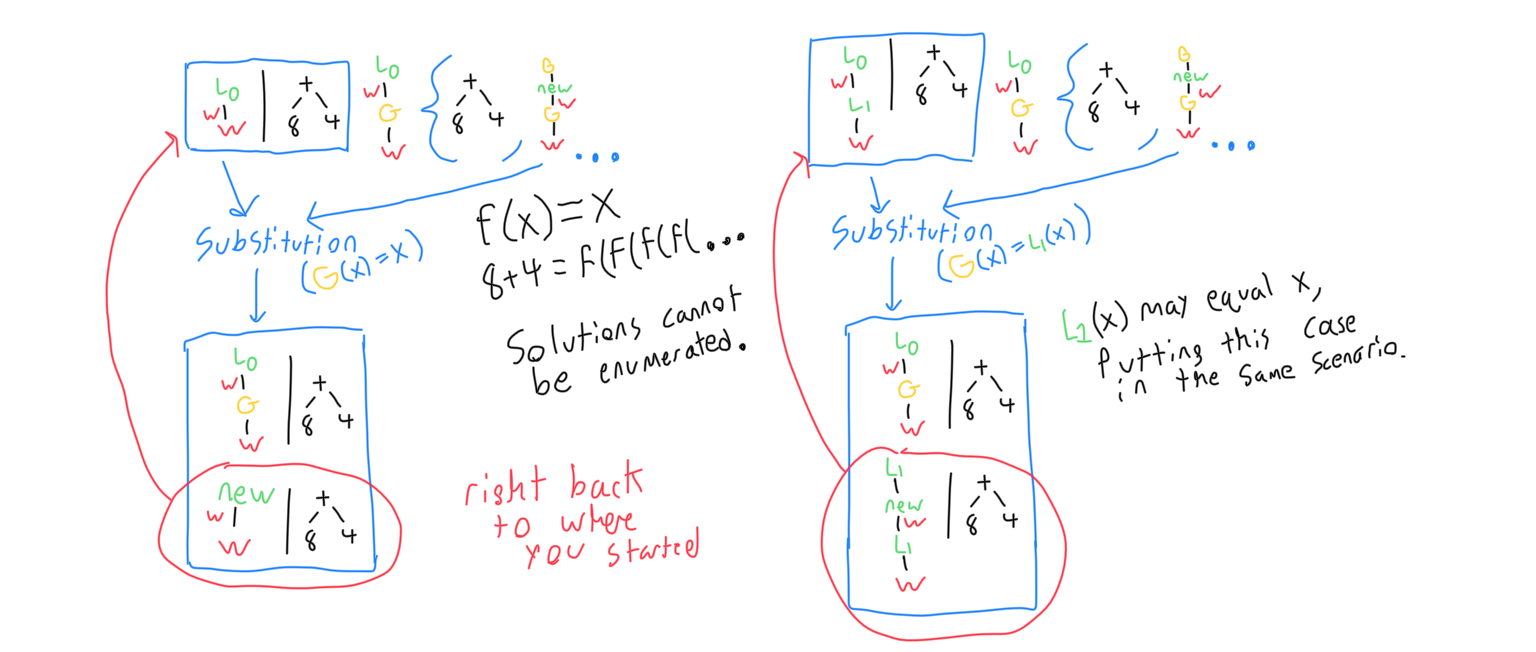

The following shows why identity functions as parameters cause problems. The program gets into an infinite loop when trying to further specify patterns. This represents the possibility of applying f(x) any number of times when f(x) is judgmentally equal to x.

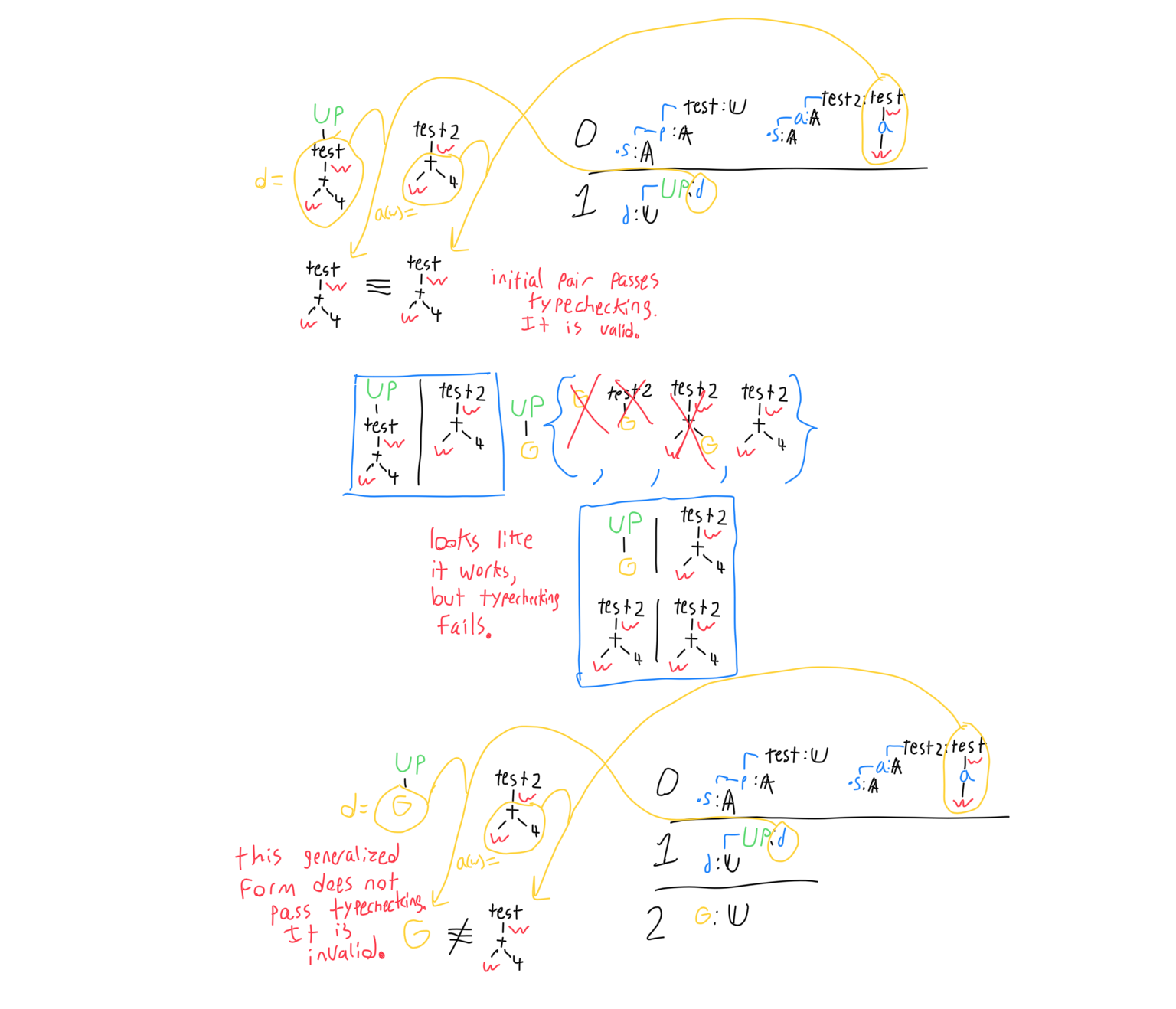

In addition to substituting the patterns back in, the new patterns also need to be typechecked. In this case, rather than automatically invalidating the binding object when the types of each side of the pair are not judgmentally equal, both types are inserted as another pair of statements. This has the same effect in most cases, but in the case where one of the types has an unknown variable in it, it can reveal a possibility that wouldn’t have otherwise be caught. In the example below, the unknown variable’s type is the same as its parameter. If a solution existed for that variable, then any statement would be true, because the solution would produce a proof for any predicate passed to it. Any complete solution for the unknown is going to be invalid, even if a valid solution exists for one instance of it.