Proof Engine structures

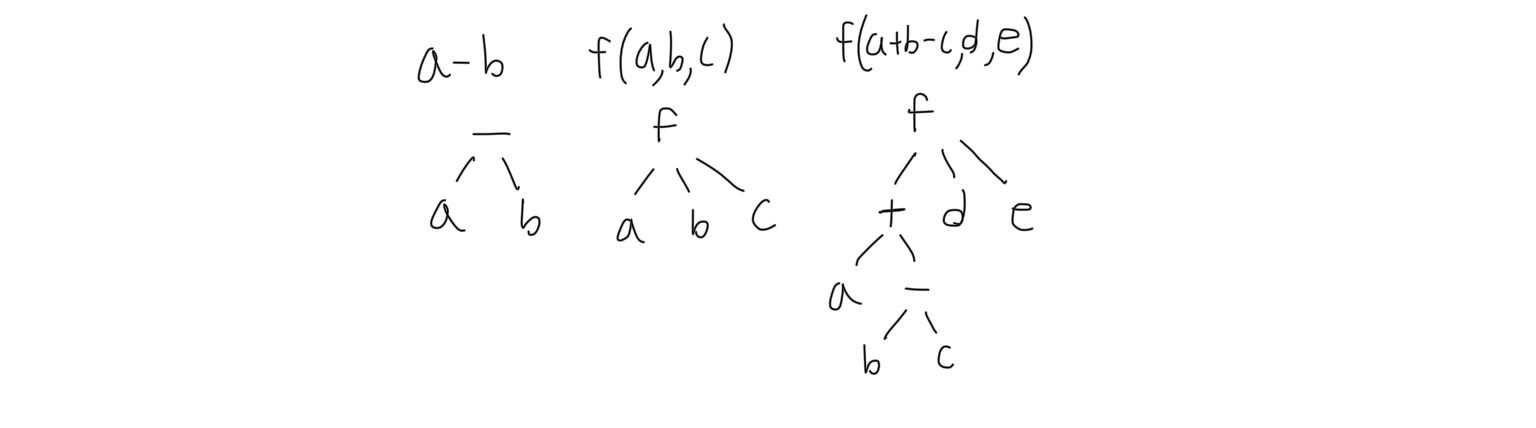

TO DO: I'm going to include visualizations from my gephi visualizer. The most basic building blocks in the proof deducer are statements. I define statements to be a kind of tree. Each node in the tree is a constant, some kind of operation, or a substitution variable. Note that statements are not necessarily numerical- they can have much more complex types than that (the type of a statement can also be represented as a statement). Examples include a-b, f(a,b,c), f(a+b-c,d,e).

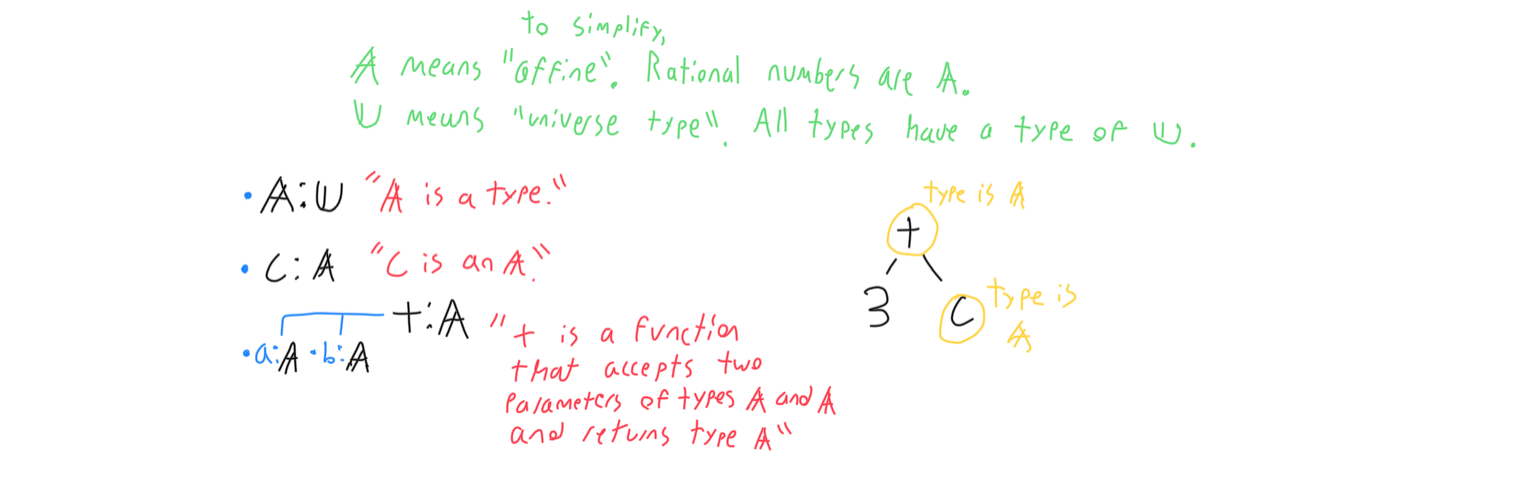

A node’s type, number of arguments, and the types of its arguments are determined by a signature, which I define. Like statements, signatures are also trees, but with key differences. When a node appears in a statement, it’s like a function call. Signatures are like function definitions.

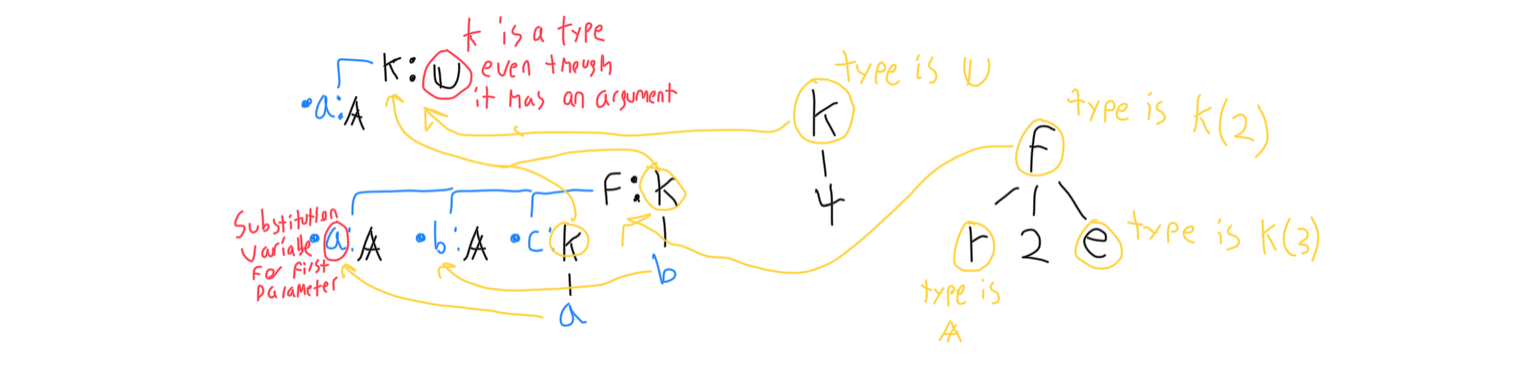

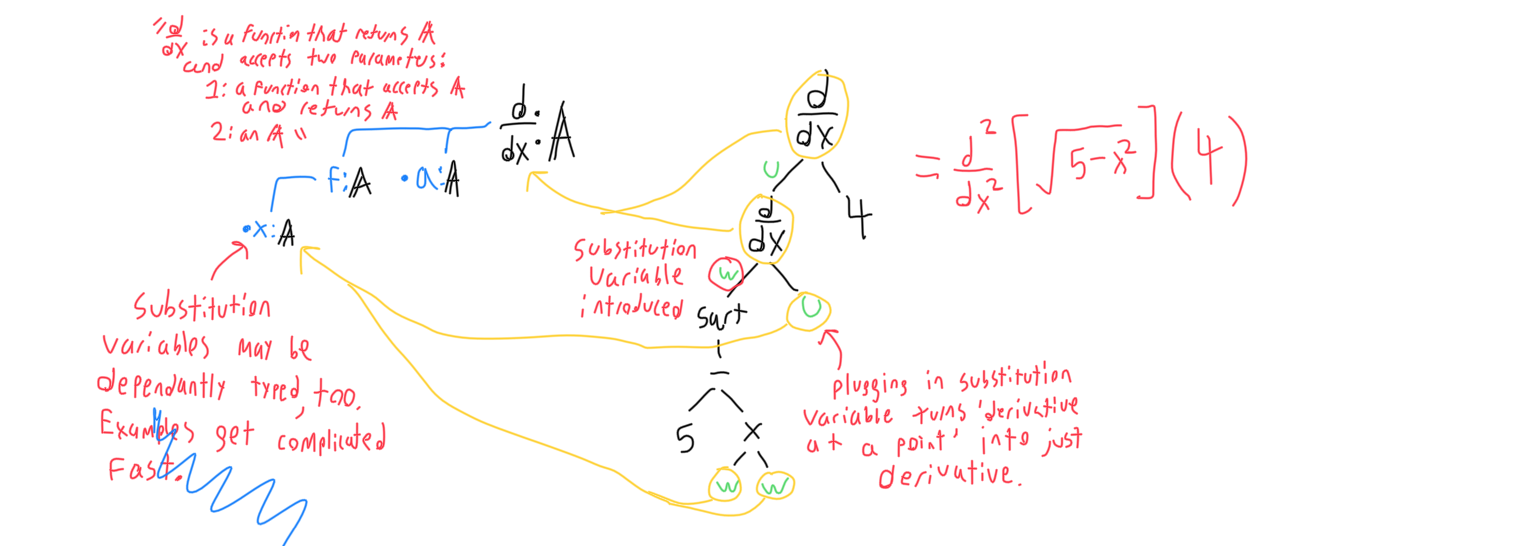

Functions may also be dependently typed. A signature’s type or the signatures of its arguments may be written in terms of substitution variables standing in for its parameters. In other words, dependently typed function have a type or arguments whose types depend on the function’s inputs. A powerful example of a dependently typed function is the reflexivity property, but to completely understand it, you’d either need some prior type theory knowledge or to read a few more chapters of this blog.

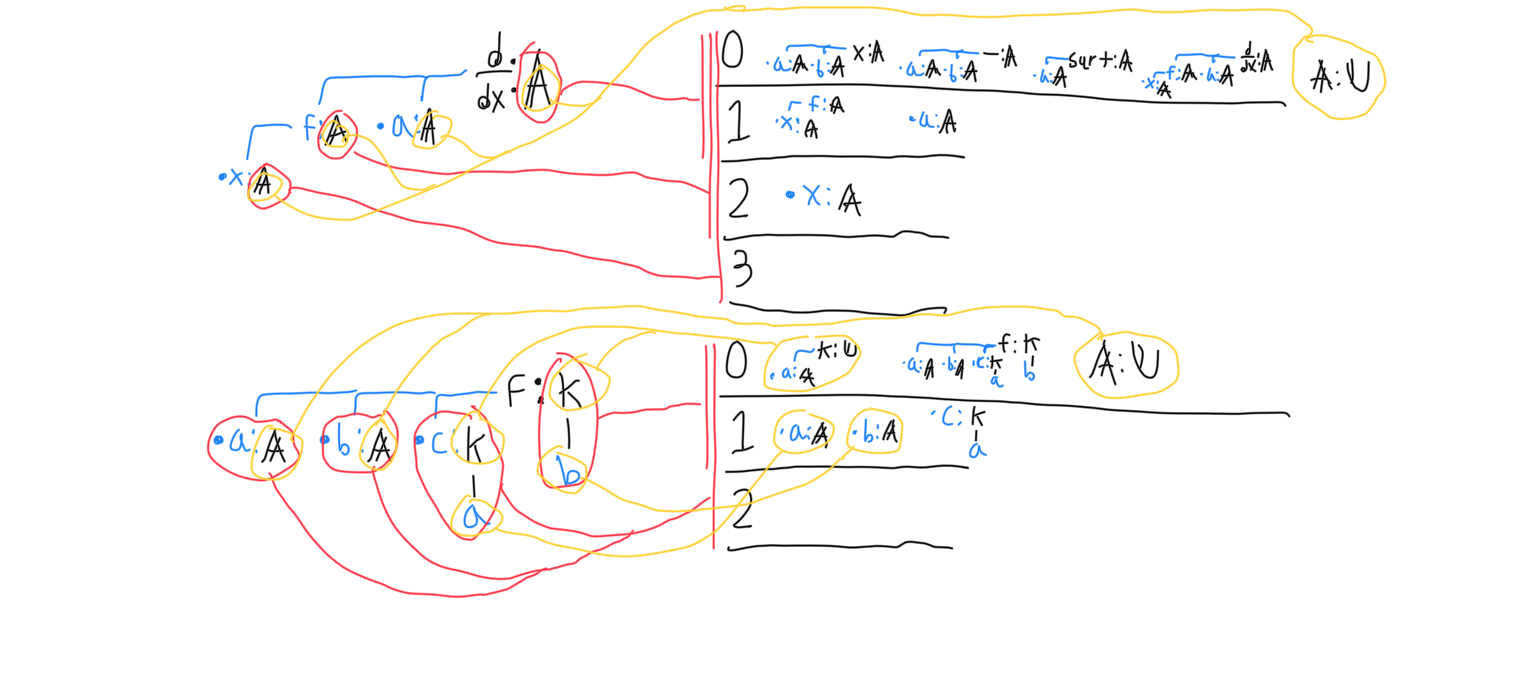

Since signatures are recursive, parameters may also be functions. To pass a function to a function, function variables may be referenced within the argument that expects a function as a parameter. This is difficult to describe in words, so the figure below shows this in greater detail. In the following example, the ‘derivative at a point’ function’s signature is shown. It accepts two parameters- the function to differentiate, and the input to the derivative. From this, the second derivative of a function can be constructed.

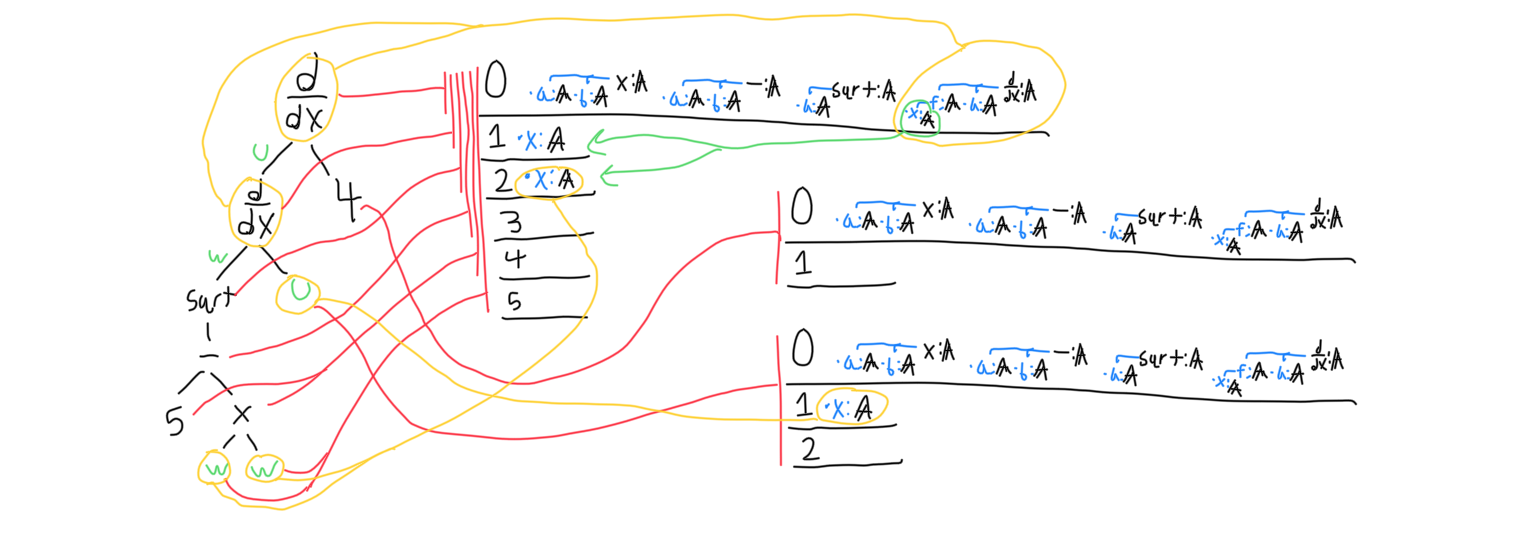

Each node may only reference signatures within its scope. When a statement is interpreted for any purpose, it is done so recursively, so that scope can be built on the way down. Scope takes the form of a staggered 2d array of signatures, so that each move down the tree adds another row to the scope. Nodes index into the scope with a pair of integers. The first row in the scope is always the complete set of type theory axioms that the proof deducer must build everything out of.

Signatures are also interpreted with a scope. Because (in the case of dependently typed functions) each child signature or the type statement may reference any of the signature’s arguments as substitution variables, a signature adds its child signatures as a new row to the scope as it is interpreted.

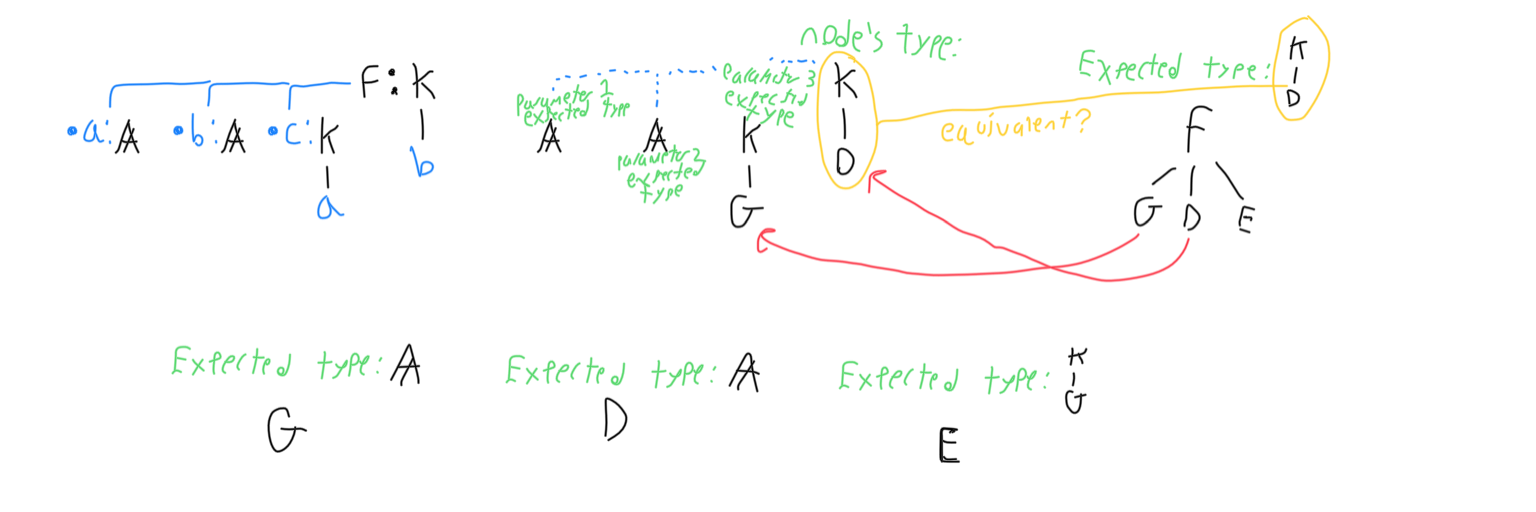

The proof deducer can be very difficult to debug. To sanitize inputs and ensure good output, statements must be type checked. Type checking involves using a signature to generate a statement’s type, and then compare the generated type with the expected type for that statement. The expected types of the node’s arguments are then generated and then the type checking is continued recursively. The proof deducer obsessively type checks all statements during development because it helps catch bugs.

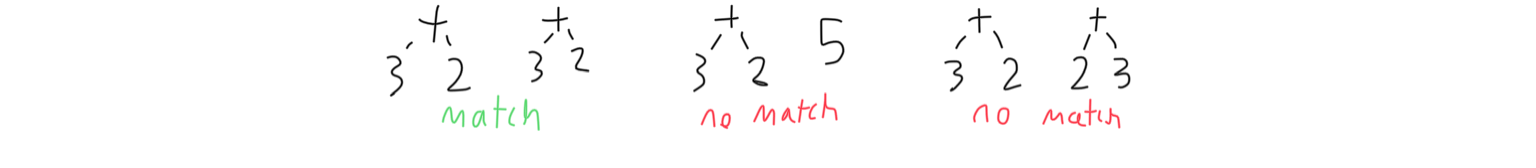

In type theory, two statements are judgmentally equal if and only if their structures are the same. Under this definition, 3+2 is judgmentally equivalent to 3+2, but not 2+3 or 5. When the program performs type checking for the purpose of sanitizing inputs or debugging, the expected type and the generated type are compared to see if they are judgmentally equal. If they are not, the program throws an exception. In other areas of the program, type checking is performed with different goals, such as setting the expected type equal to the generated type to solve for unknowns.