Custom Language Compiler

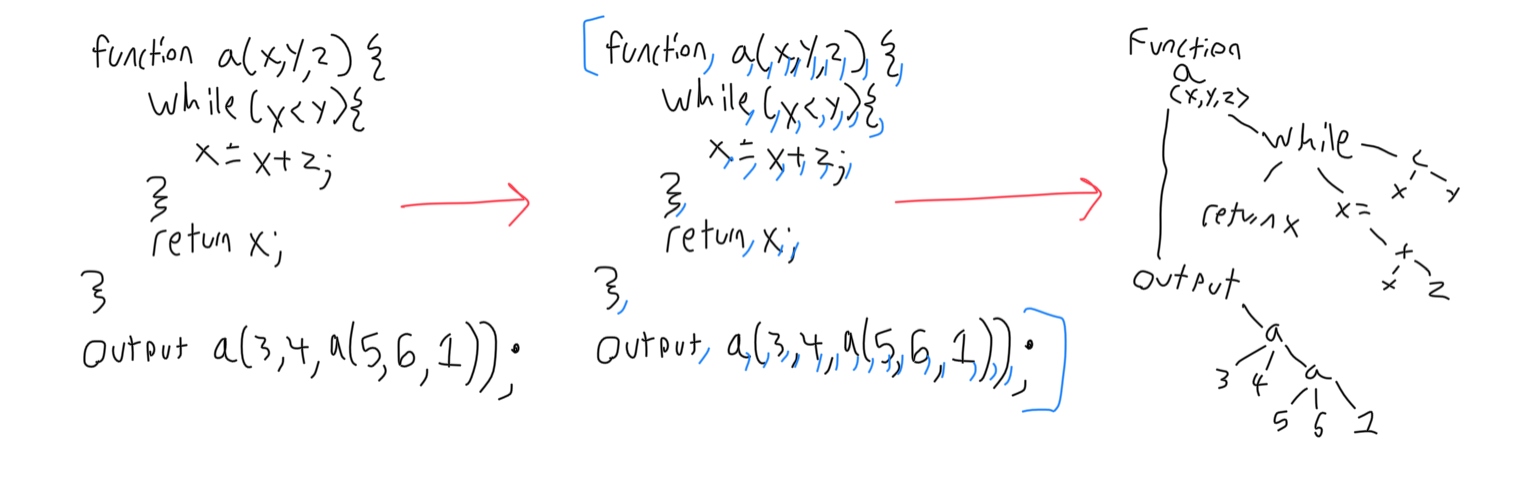

This computer cannot accept normal instructions, which means I had to write a compiler that can produce the special kind of assembly language that the computer can execute. Rather than compile an existing language, I made a very barebones language that I named K. The language is first tokenized, and then interpreted into an intermediate structure which can be very quickly turned into my assembly. For more about parsing, see the proof software project.

The intermediate structure representation of the program is a tree. For this simplified language, there are expression nodes and structure nodes. The root node of the program is a structure node. Structure nodes are for blocks of code such as loops, conditionals, variable declarations, assignments, and functions. Expression nodes are for connectives within an expression such as addition, subtraction, variable reference, and the like.

-

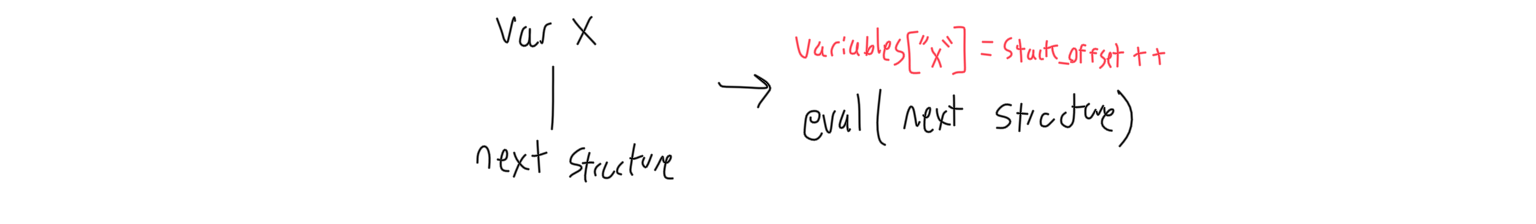

Variable declarations are the simplest structure node. They are made to chain together and do not become assembly language, only influence the stack, which changes the way later structures are parsed.

-

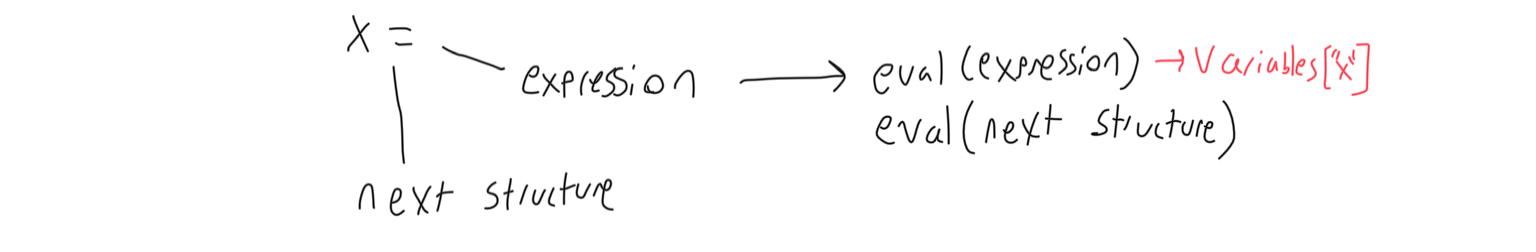

Assignments are the next structure node. I make assignment a structure rather than an expression to simplify the language. They translate very simply- they just evaluate the expressions they contain into the variable.

-

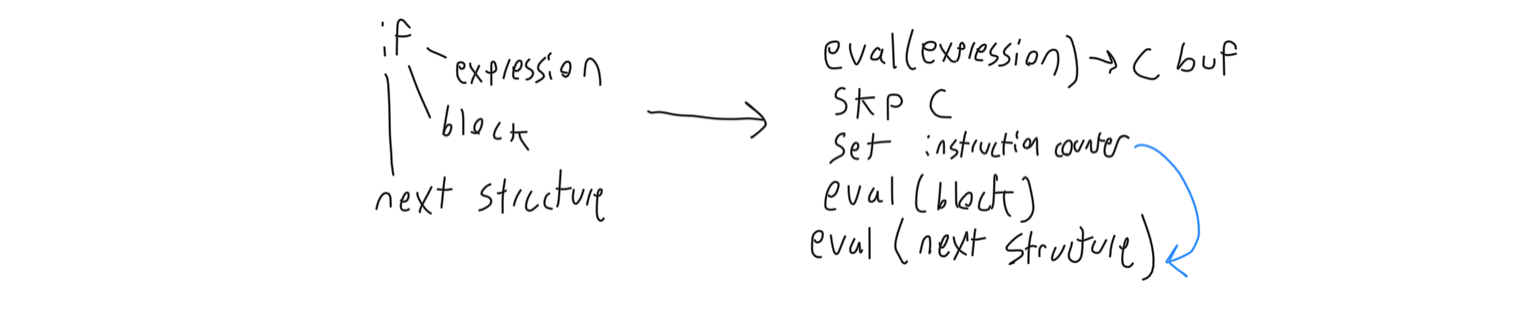

Conditionals are simple, too. First, they evaluate their expression into the C buffer. Then, they generate an SKP instruction for the C buffer followed by a SET instruction to the instruction counter (essentially a JMP). Then, the conditional’s body is evaluated. Now that the number of instructions that the body evaluates to is known, the JMP instruction is revisited to set its destination.

-

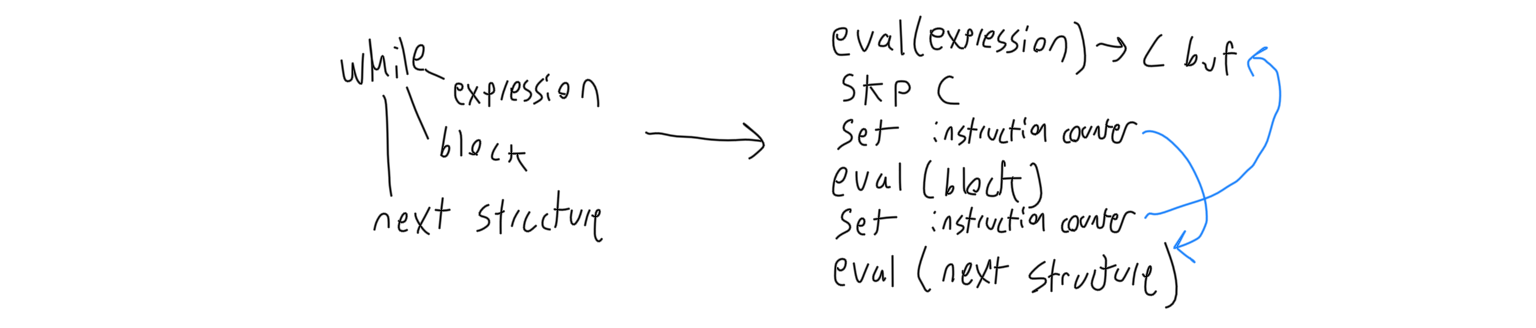

Loops are similar to conditionals. They have another JMP instruction added after the body instructions that sends the counter back to just before the expression is evaluated.

-

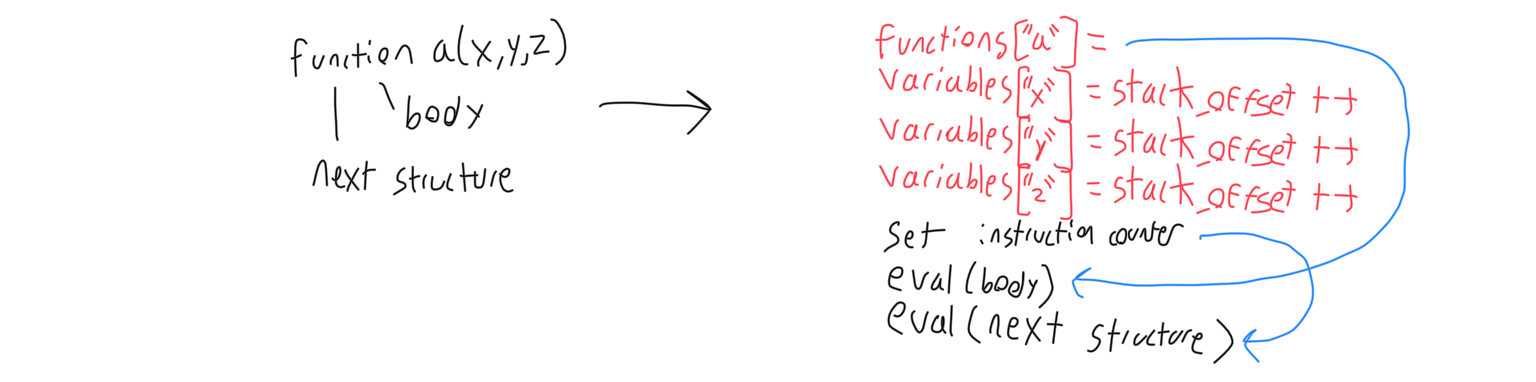

Function declarations turn into a JMP instruction to ensure that the function doesn’t run when it is declared, and then each parameter turns into a variable declaration on the stack. When the function is called, any arguments will be evaluated into the first words onto the stack.

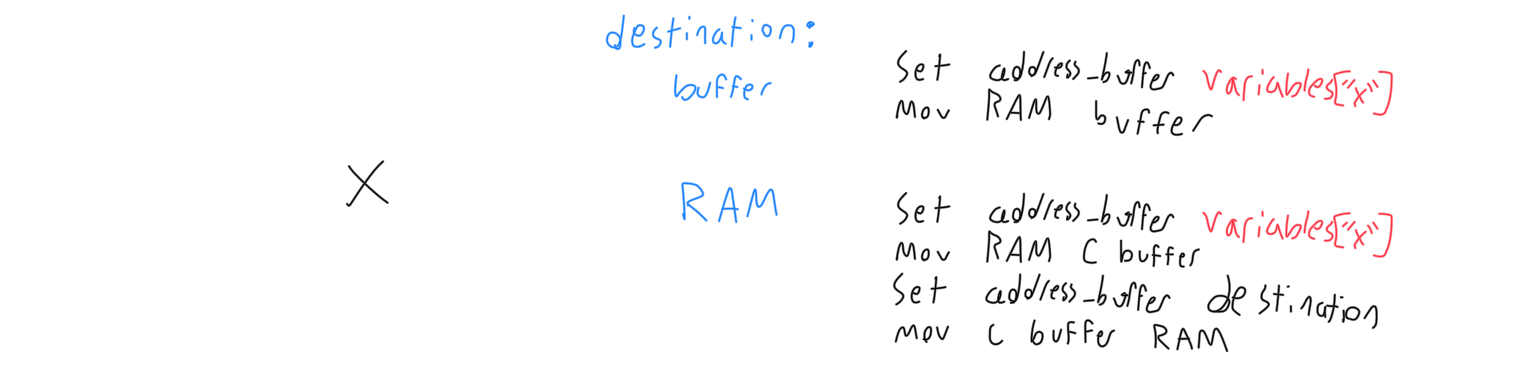

As opposed to structure nodes, expression nodes are given locations to leave the expression result, be it a buffer or a location in RAM. This is how assignments work; all they do is pass the variable’s location along to their expressions. When the location is in RAM, the program assumes that the address buffer will be left at that location after the expression finishes.

-

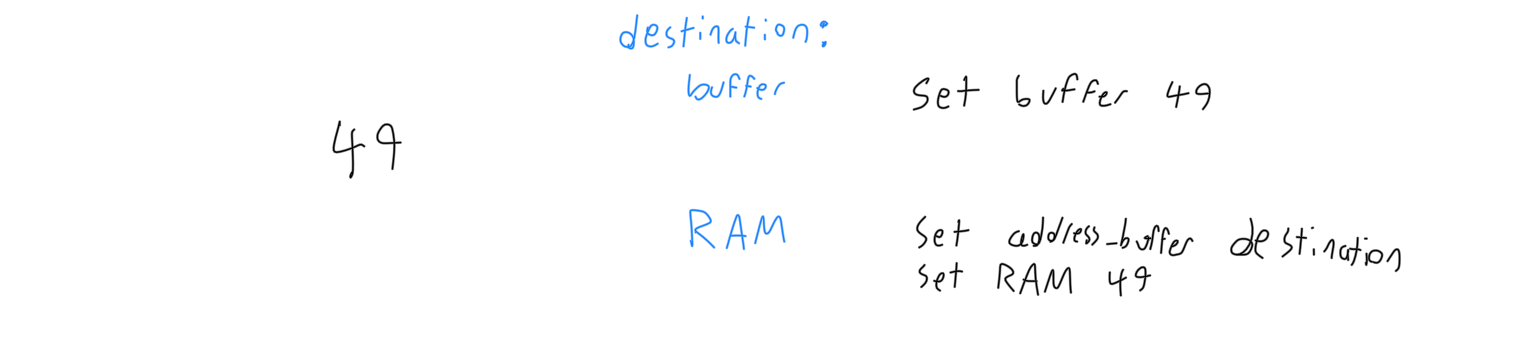

Constants are the simplest expression nodes. They turn into SET instructions.

-

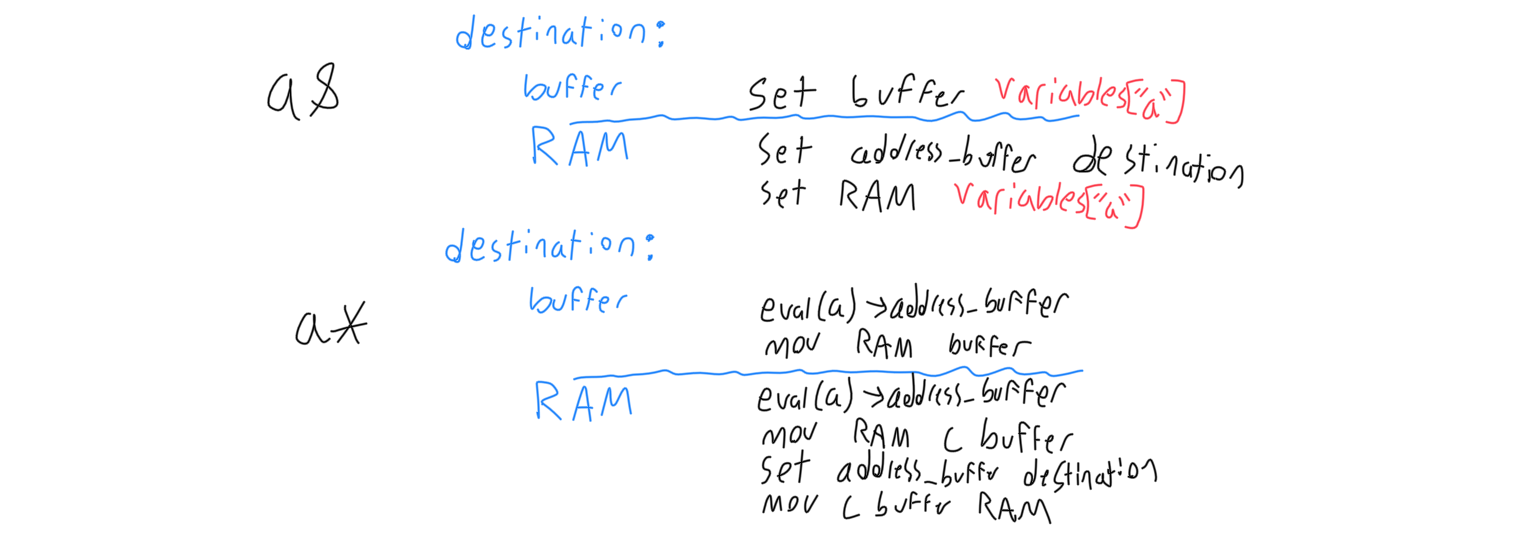

Variables are much more complicated. Each time the program wants to access a variable on the stack, it must add the stack offset to the variable’s position relative to it, and set the address buffer to the result. When looking at the instructions generated by my compiler, most of the computer’s work happens to be shuffling buffers for this purpose. If I were building the computer over again, I’d change the address buffer to be two buffers connected by a full adder. That way, one buffer could contain the stack offset, cutting out ~70% of each program’s instructions. Allowing one of those buffers to be read from would improve it even more, providing a more elegant way to increase or decrease the stack offset.

-

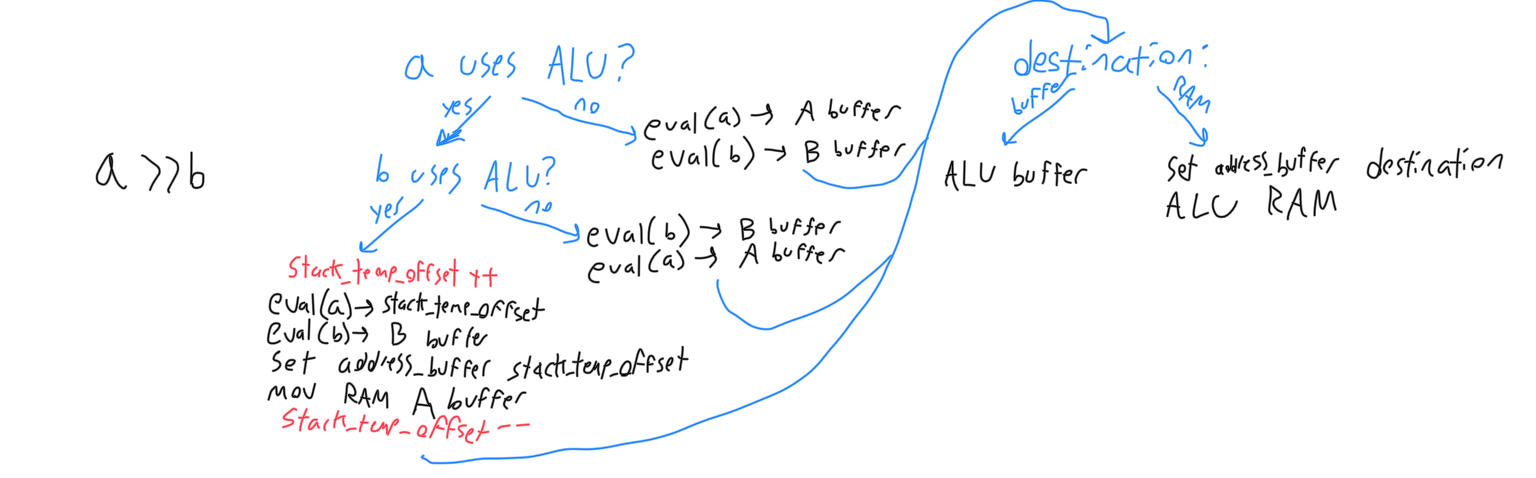

While parsing binary expressions, an additional offset on top of the stack offset is incremented to allow words to be temporarily stored in memory, if they need to be. The following flowchart describes the optimizations done to a binary expression (if possible)

-

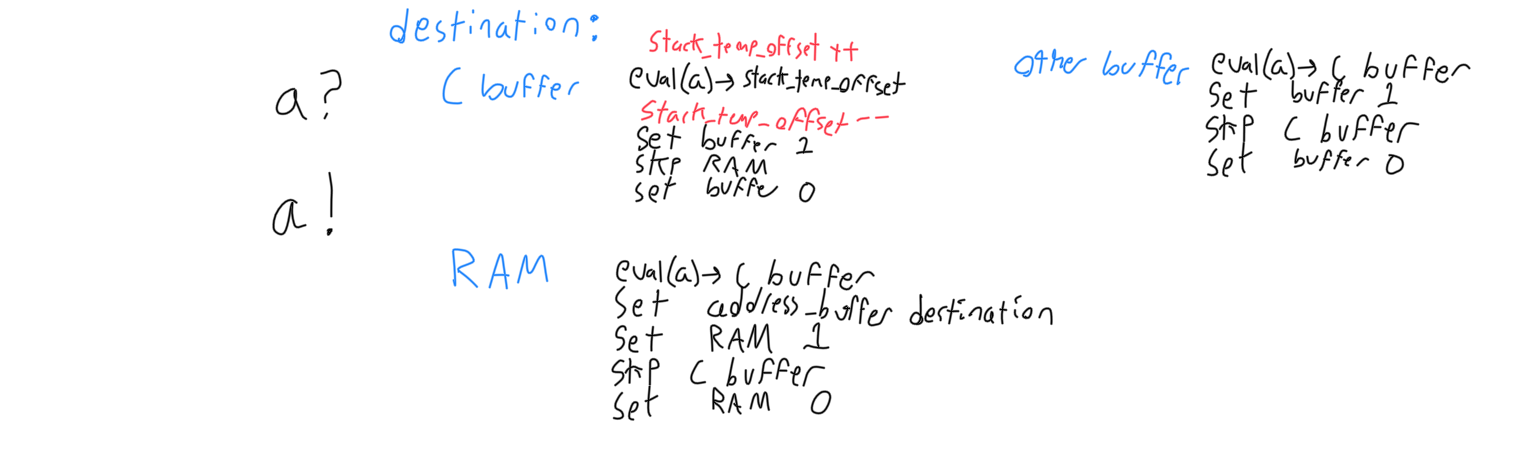

The program also introduces two operators for clamping values from 16 bit integer range to a 1 or 0. Essentially, a ‘truthiness’ test, and an inverse truthiness test.

-

The program also supports reference and dereference operators. Pointers are the same data type as any other word, and there are no protections to ensure that the machine doesn’t change memory in use by the OS. Reference operators are are turned into constants.

-

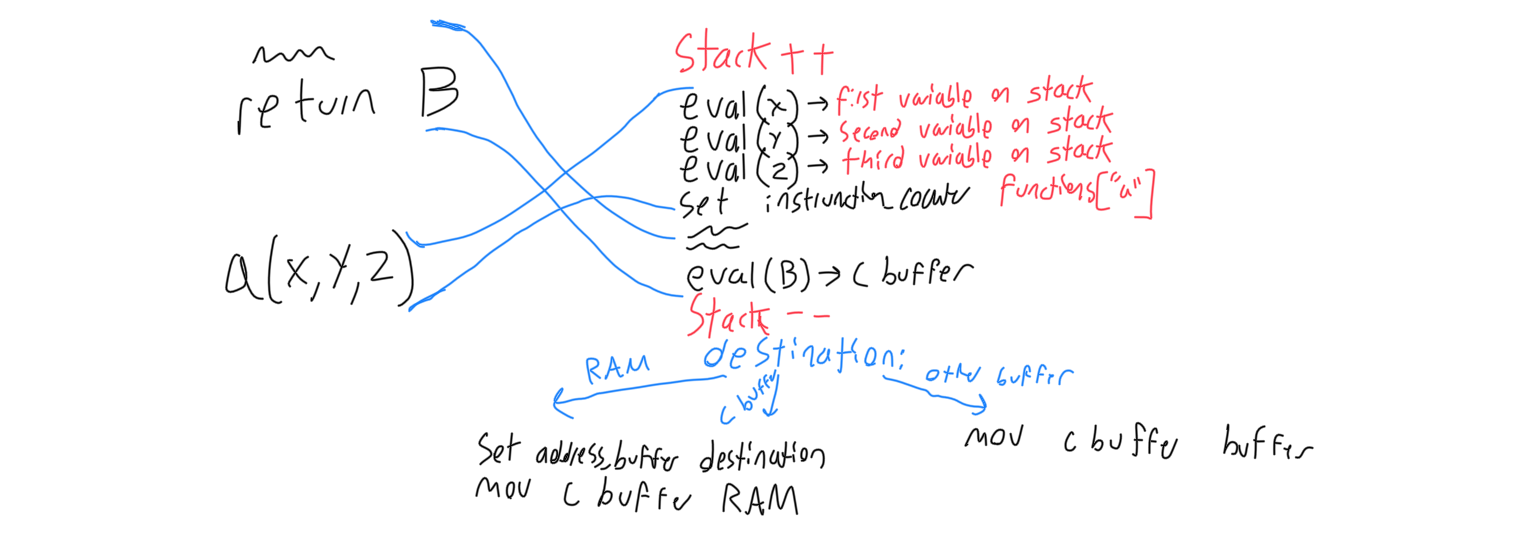

Function calls must add onto the stack offset, leave the current position in instructions in ram, and then evaluate each of its parameter expressions into the stack variables they correspond to inside the function’s scope. After that, the function jumps to the function’s position in the instructions. Once the function reaches its return statement, it subtracts from the stack and leaves the function’s return value in the C buffer.

- I was originally going to implement a heap with memory allocation and reallocation operators, but I realized that each one would turn into a lot of instructions and ram usage. The computer’s ALU occasionally mishandles operations, so small programs will execute fine, but any program over 80 operations isn’t worth trying. I spent a long time trying to fix that problem, because it would allow me to create a whole OS for the system, but the project got pushed to the wayside when summer ended.